This page contrasts with ‘wings & tails’ in being largely theoretical and single-author.

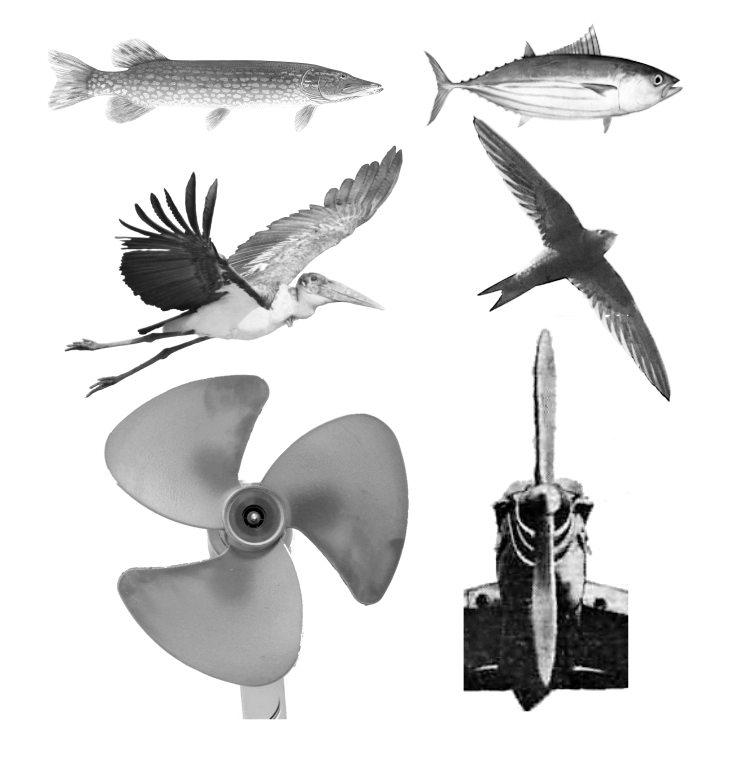

What connects the way fish fins, whale flukes, bird and bat wings, and propellers move to provide thrust? Why do pike have broad tail fins, but tuna have narrow? Why do vultures and pheasants have broad wings with ‘fingered’ wingtips, but swifts have narrow, simple wings? These questions cannot be answered by thinking only about aeroplane wings. However, they can by using simplified propeller theory, with results evident from fan and propeller design: efficient thrust production at low speeds – obvious for the pike, but also vital for loaded or rapid take-off in vultures and pheasants – requires broad, high-lift foils like a desk fan. At high speeds, narrower foils produce thrust efficiently, accounting for tuna, swift and Spitfire propeller design.

This paper draws a parallel between the motions of fins, wings and flukes when producing thrust to the geometry of an efficient propeller. It shows that animals move their ‘foils’ in certain ways not because of some interaction with the vortex wake, but because it provides the balance between ineffective thrust production (too slow) and excess power demand (too fast). It does suggest that animals flap their foils a little slower than would be ideal in terms of aerodynamic efficiency, but that this loss is relatively small. And there are many reasons why oscillating your wings or fins a bit slower might be advantageous – including avoiding the costs of accelerating masses and improving the conditions for muscles to provide power economically.

This paper [in press] extends the propeller analogy to swimming fish and flapping birds to account for the observed relationship between animal wing and fin shape with speed.

The conclusion is that relatively narrow, simple wings are efficient – and so provide a high thrust for a given power supply – at high speeds. In contrast, relatively broad wings with high lift coefficients (thick, cambered, with tips either slotted (see vulture wingtips) or sharp and swept (fan and marine blades)), are efficient – and so again provide a high thrust for a given power supply – at low speeds. The demand is the same: thrust, for a given power supply; and the mechanism is the same: aerodynamic efficiency. But the required foil geometries are very different. As is the use to which the thrust is put: overcoming high drag at high cruising speeds, or accelerating towards prey (pike) or in take-off (pheasants, vultures, etc.). The reason behind the efficiency of foil shapes varying with speed is developed below, but it comes down to requiring the same relationship between flap speed and forward speed as found for wings, fins, flukes and propellers in the first paper.

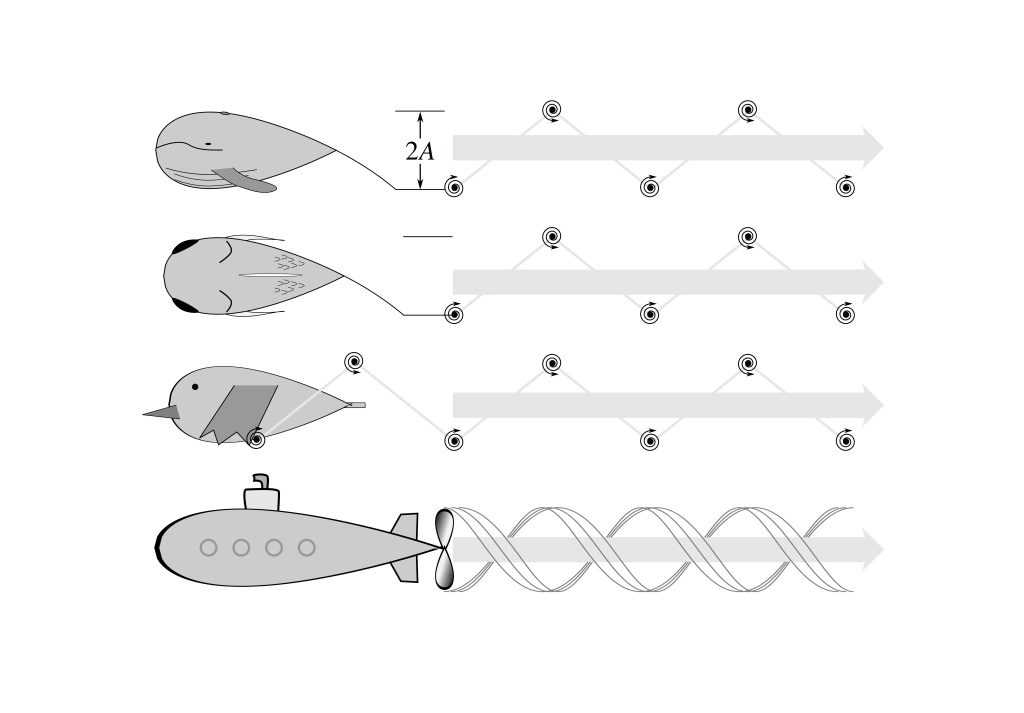

The videos show the geometry of the foil of a fish, whale, aeroplane, ship or bird travelling forward with speed U and flapping speed V. The lift (light blue) acts perpendicular to the resultant velocity (green); the drag (yellow) acts parallel to it. Thrust drives (orange) the animal or craft forward, while a costly force C (dark blue) demands power from the motor. The ratio of useful power (T.U) to motor power (C.V) gives the efficiency.

The first video shows the effect of varying the lift to drag ratio. Higher lift:drag ratios are better: they result in more thrust and less power; they result in a higher efficiency. Here, the lift:drag ratio is assumed to be a property of the foil, and independent from to be the other parameters being considered. This is not quite true, but it is a useful starting point.

The second video shows the effect of varying tip speed ratio. This is the ratio of flap speed V to forward speed U, and has an equivalance in terms of ‘Strouhal number’ as described in swimmers and fliers, and ‘helix angle’ in propeller terminology. As forward speed U is constant here, it is directly related to flap speed V. At low tip speed ratio – low flap speed – little thrust – in extreme cases even negative – thrust is produced, and the foil has a very low efficiency. At high tip speed ratio there is higher thrust but also higher power: efficiency is better, but at very high tip speed ratio aerodynamic efficiency falls slightly. The observed range in biology (fish, bats, birds) is somewhat below that predicted, but the consequences in terms of efficiency are minor.

The third video keeps lift to drag ratio realistic (6) and the tip speed ratio close to ideal for efficiency (1) and shows what would happen if the animal swam or flew forward faster. Flap velocity would increase, maintaining the efficient tip speed ratio. Thrust would increase, but so would motor power.

But what if the animal had been using its full muscle power at the slower speed? The power demand at this higher forward speed exceeds the supply: what should change? If the tip speed ratio was reduced, power would be reduced, but so would efficiency, so the thrust would not be ideal. Keeping the tip speed ratio constant requires that the foil produces less force per speed: it must have a lower area or lift coefficient. The next video shows the process of reducing that parameter to match the initial power constraint while maintaining the efficient tip speed ratio.

So we now have a foil producing the best thrust it can for a given power at high speed – a relatively narrow foil as seen on tuna, swift and underpowered propeller aircraft such as the early Spitfires. The next video show the effect of maintaining the efficient tip speed ratio with reduced forward speed.

While efficiency is maintained, forces are reduced, and so thrust and power goes down. Now, less thrust is being produced than should be possible for a given motor power supply. Changing the tip speed ratio would harm the efficiency: the next video shows how an increasing foil area and lift coefficient can be tuned to match the available motor power supply and maximise the thrust capability:

At low forward speeds, a high foil area and lift coefficient allows a high efficiency and high thrust capability for a given power supply. Correlates with high area and lift coefficient – perhaps a low aspect ratio or thick, cambered wings, or wingtips with slats or sharp, swept leading edges – would reduced the lift:drag ratio. This interaction is not considered here quantitatively; qualitatively, however, it would somewhat soften the predicted relationship between speed and area or lift coefficient.

This line of reasoning does not suppose that the primary – selected-for – function of all propulsors is to overcome body drag during steady forward progress. Instead, it assumes that selection has acted to allow the maximum thrust for a given power supply and speed. What that thrust is used for obviously scales: the fast tuna must overcome a great deal of body drag to maintain cruising, while the slow pike, pheasant or vulture must accelerate rapidly to catch prey or take off rapidly from the ground.

The above four movies are combined here:

A powerpoint presented at The Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology (2026):

LabVIEW code for hand-tuning of parameters here: