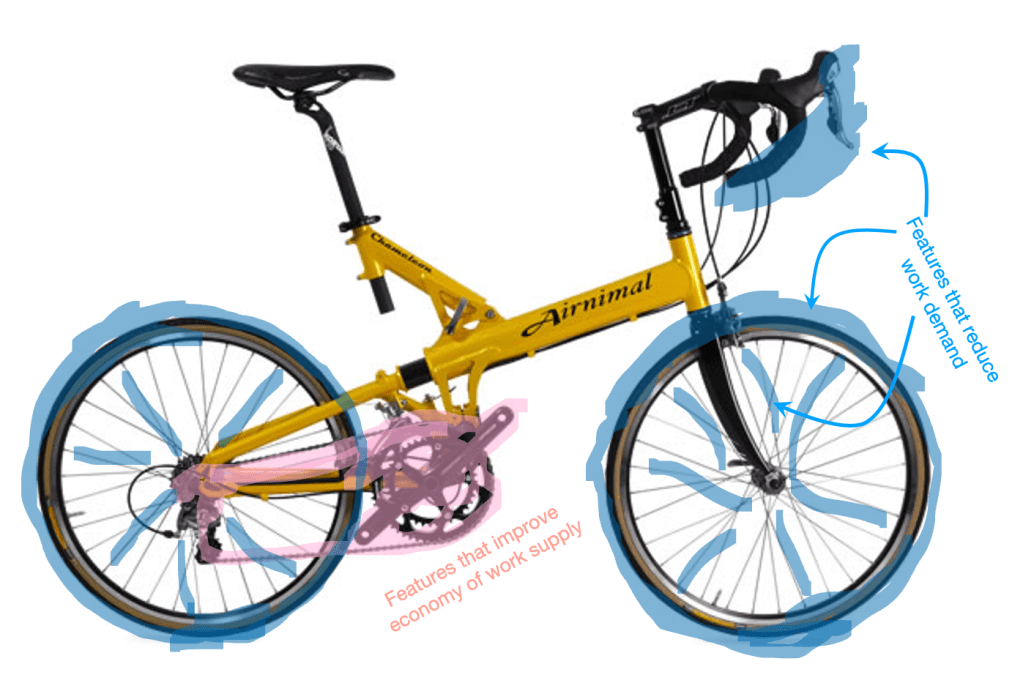

Legs can be thought of as vehicles, machines that perform the tasks of supporting body weight as it translates with both low mechanical work demand and economical work supply. Design for these tasks is clear in the case of a bicycle:

This paper considers human leg muscles, and the structures and mechanisms they produce during a running stance, in terms of their contributions to these two functions. Just as bicycle spokes – as part of a wheel – function to avoid mechanical work demand by supporting vertical forces during horizontal motions, so do a series of muscles that get pulled through changes in geometry as the body travels over the foot. Also, just as bicycle spokes do not do any work because they resist forces without stretching or shortening, so can the muscles (mostly): the series of muscles that support body weight do so without changing length (mostly).

Something about human legs allow the body to ‘slide’ somewhat over the foot: measured forces (blue) are nearer vertical than forces that would go in line with the leg (red), meaning that mechanical work is avoided.

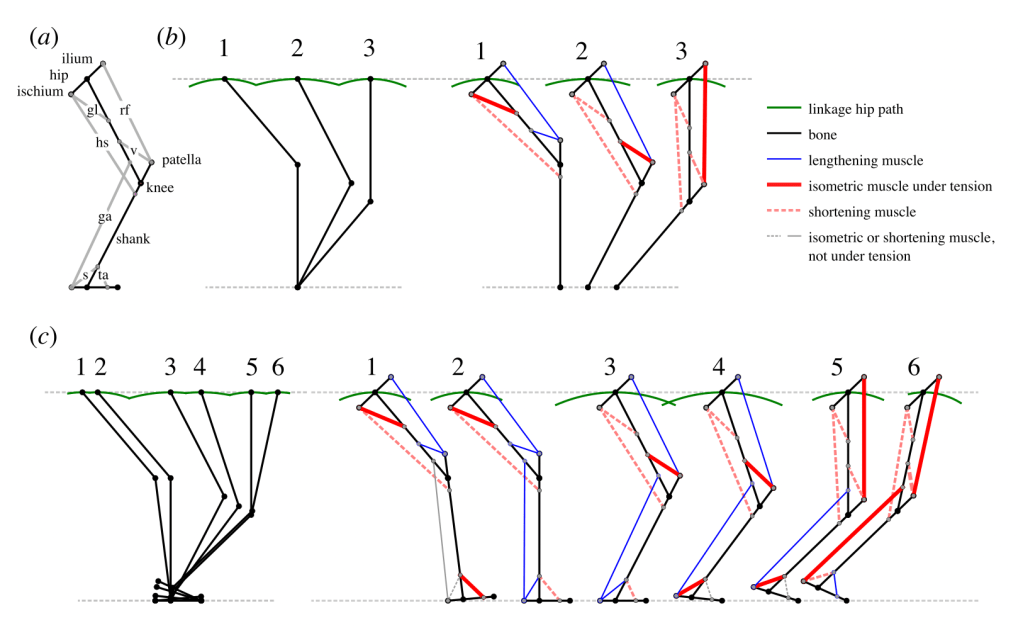

This is a simple 3-part pelvis-thigh-shank model that supports (mostly) horizontal motions with (mostly) vertical forces. The muscles in red (gluteus, then vastus, then rectus femoris) come under tension at their longest lengths, so simply need to resist being pulled to produce the sliding, work-avoiding motion.

The second function of the leg, to enable muscles to produce work economically, should not interfere with the first function. Just as the bicycle pedal and gears allow the muscles to work well, but do not change the economical round shape of the wheels, muscles that power running should not alter the work-avoiding geometries. Muscles are limited in the amount of power they can generate at any instant so, for a given mechanical work to be supplied, smaller muscles are needed, or less muscle activated, if they can shorten over a longer period. The distance between hamstrings origin (behind the hip) and insertion (under the knee) gets shorter over the whole of stance. This means that, if the hamstrings were to be under tension all this time, they could be contributing mechanical power both economically (as they have a long time to do the work) and without altering the work-avoiding geometries imposed by the muscles that are loaded but are not changing lengths.

The geometric loading of gluteus, then vastus, then rectus femoris can be demonstrated using a model with paper muscles. Note also that the hamstrings become increasingly slack as the body slides forwards.

The same ideas can be extended to more complicated models. Adding the foot and imposing heelstrike running results in an even smoother path of the body:

Note that these models do not include anything to do with springs. The equivalents of bicycle tyres and suspension are deliberately missing. But it is easy to imagine where springs – such as the Achilles – might become unloaded and recoil helpfully in late stance.

These models of the human leg in running, and the view of muscles acting either as bicycle spokes to avoid work demand, or to contract over long periods without changing the underlying geometries, begin to give tractable answers to several puzzles. Why are legs so complicated? Possibly because of our evolutionary heritage, possibly because legs have to be adaptable and perform many tasks other than running… But at least in terms of control, having more than one motor per joint appears to be wasteful. And what benefit might there be to ‘antagonistic’ muscles imposing tension at the same time? It would appear odd that the hamstrings and quadriceps should pull against each other. But the multiple single- and two-joint muscles and co-activation of antagonists begins to make some sense even in steady running if legs are ‘designed’ to perform the two functions – weight support during carriage and economical work supply – at the same time.

Talk. Also available here.

Powerpoint with notes from SICB 2025 conference. Slides, graphics, animations may be adopted and adapted. Contact jusherwood@rvc.ac.uk if you are interested in obtaining physical demonstrators.